Wrongful convictions in New Jersey

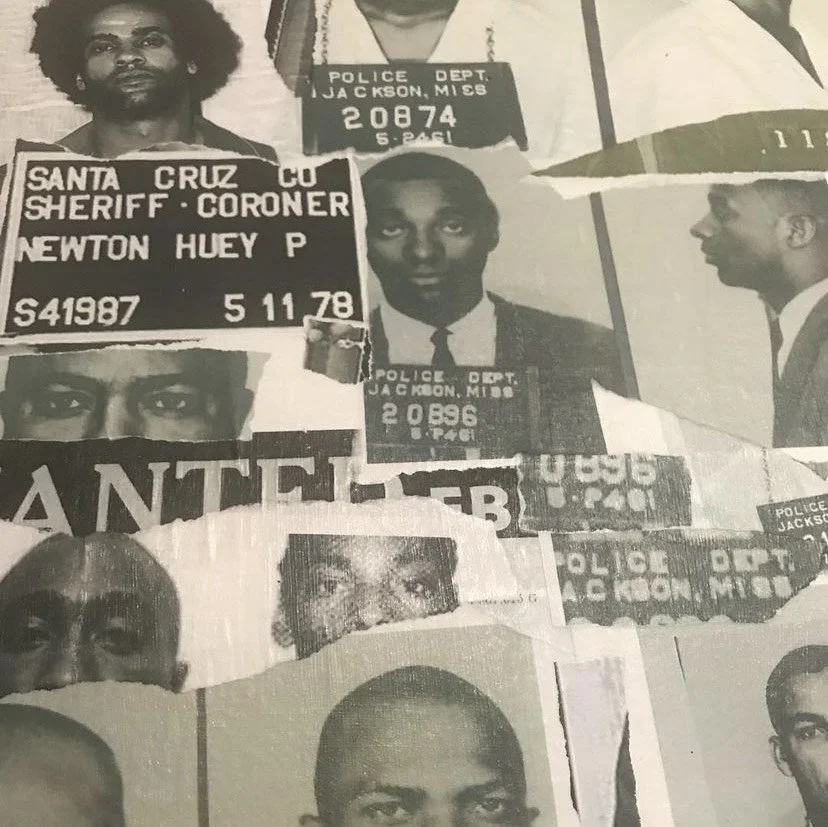

Artwork by artist Xplorefreedom.

The following is a deep dive into wrongful convictions written by Prof. Matthew Barry Johnson and Angeles Tovar Galeano

NEWARK, NJ—In the past three decades, new questions about the integrity of the justice system have emerged as a series of convicted 'criminals' have proven their innocence.

The Innocence Project at the Cardoza Law School in New York, the National Registry of Exonerations, and other innocence advocacy groups have documented these exonerations and the dramatic impact DNA science is having on the criminal justice system.

Exonerations have occurred across the United States, and there have been several disturbing wrongful convictions here in New Jersey. During the campaign to abolish the New Jersey death penalty, some of the most critical testimony was provided by New Jersey exonerees, David Shephard, James Landano, Nate Walker, and Byron Halsey.

These men were able to provide firsthand accounts of the justice system errors that produced their years of imprisonment for crimes they did not commit. Reports indicate African Americans are at increased risk of wrongful conviction when compared with white citizens. While this may be related to the general overrepresentation of Black defendants among those facing criminal prosecution, there are likely other specific ways racial bias contributes to wrongful conviction.

Prior to the DNA era, the question of wrongful conviction was usually framed as whether it occurs. Now the question is how often it occurs and how can we prevent it.

James Sweeney

Legal scholars studied wrongful convictions prior to the DNA era, but often their work did not receive adequate attention. Borchard's 1932 text "Convicting the Innocent: Errors of Criminal Justice" is recognized as the first systematic study of wrongful conviction. Borchard presented many cases of wrongful conviction in the US. One New Jersey case illustrates problems that still exist today.

In 1926 James Sweeney was tried for his role in a high-profile bank robbery in Elizabeth, New Jersey. A gang of bandits with machine guns robbed an armored truck in broad daylight. The robbery and murder resulted in tremendous press and public pressure on the police for arrests. Circumstantial evidence led to James Sweeney whose alibi (provided by his mother and others) was insufficiently persuasive to protect him at trial. His conviction was secured by several eyewitness identifications.

A post-conviction investigation by Sweeney's defense counsel uncovered errors by prosecution eyewitnesses, and it was noted that Sweeney strongly resembled one of the actual perpetrators. Sweeney was subsequently pardoned.

This case illustrates that 90 years ago, eyewitness misidentification was crucial in this high-profile wrongful conviction. Also contributing to the eyewitness error was the press and public pressure to clear certain crimes and the fact that alibis are often discounted.

Eyewitness Misidentification

More recent cases demonstrate that eyewitness misidentification remains a leading cause of wrongful convictions. While eyewitness identification is considered to be very compelling evidence of guilt, there are a number of factors that interfere with eyewitness accuracy. Some of these factors are visual ability, lighting, distance, stress, and weapons focus.

In some cases, another complicating factor is cross-racial identification. That is the difficulty most people have correctly identifying a stranger from a different racial group. Three well known New Jersey wrongful convictions illustrate cross-racial eyewitness misidentification.

Nate Walker

In 1976 Nate Walker, an African American man from Newark, went to trial accused of the rape of a white woman who picked him out of a line-up. Even though Walker had an alibi, confirmed by a time clock, he was convicted at trial and sentenced.

Fortunately, a New Jersey appellate court released Walker on bond in 1978 noting a legal technicality. However, the New Jersey Supreme Court overruled the appellate order and Walker fled the state in 1979 rather than return to prison. Walker was later apprehended by the FBI in California and returned to New Jersey prison in 1982.

He was eventually exonerated through the advocacy of Centurion Ministries, a Princeton, New Jersey organization dedicated to freeing innocent inmates. A simple blood test was all that was needed to confirm Walker's innocence. He was released in 1986. His case was covered extensively in the March 1987 issue of Ebony Magazine

David Shephard

David Shephard, another Black man from Newark, was also wrongly convicted of the rape of a white woman. In 1984, Shephard became a suspect because the victim's car was abandoned near the Newark Airport where Shephard worked the night shift.

Shephard agreed to be questioned by two detectives who approached him one morning when he was leaving work. Through lengthy questioning, he continually denied involvement or knowledge of the offense. What Shephard did not know was that the police had secretly brought the victim to his job, and she had identified him as one of her attackers.

Despite his mother's testimony regarding his whereabouts at the time of the offense, he was convicted at trial. Shephard entered prison without a high school diploma but became an effective jailhouse lawyer who wrote his own legal briefs arguing for DNA testing of the evidence. Shephard's appeal was granted which led to DNA testing. The results confirmed the victim's account that there were two assailants, but neither was Shephard. Shephard was released in 1994.

McKinley Cromedy

A white female student was raped and robbed at Rutgers University-New Brunswick in the summer of 1992. She was examined at a medical center and the police took a report. By chance in April of 1993, the victim saw McKinley Cromedy on the street and believed he was the rapist. She notified the authorities and Cromedy was immediately picked up. The victim confirmed the identification shortly thereafter from behind a one-way mirror.

During the trial Cromedy's attorney requested a special cross-racial jury instruction, that is for the jurors to consider the increased likelihood of error associated with cross-racial identification. The judge denied the request and Cromedy was convicted.

Cromedy later won an appeal, and the New Jersey Supreme Court ordered a new trial noting the cross-racial identification instruction was warranted because the only evidence linking Cromedy to the offense was the victim's identification (State v. Cromedy, 1999).

Prior to the new trial, DNA testing found that Cromedy was not the source of the semen from the offense. Cromedy was released in 1999. Certain vagaries of eyewitness identification are illustrated in the Cromedy case.

McKinley Cromedy’s photo was one of several the rape victim was shown by police just after the attack. Thus, when she saw Cromedy on the street months later, she associated him with the rapist and misidentified him. This is referred to as the ‘mug shot exposure effect,’ where a face is recalled with incorrect recall of where the face was initially seen.

Dion Harrell

Eyewitness misidentifications are not always cross-racial. Dion Harrell, a Black man, was misidentified by a Black rape victim in Long Branch in 1988. The victim was attacked after leaving her job at a fast-food restaurant one night. Three days later she saw Harrell in the parking lot of the restaurant. She believed he was the rapist and notified the police. She identified Harrell again at the police station and this led to his trial conviction in 1992.

He was sentenced to eight years and released on parole, as a registered sex offender, after serving four years. Due to his status as a registered sex offender, he faced continuing obstacles in finding employment and maintaining stable housing.

The New York Innocence Project agreed to take his case in 2013 and this led to laboratory testing of the crime scene evidence that proved Harrell was not the rapist. He subsequently was awarded compensation for his wrongful conviction and the adversity he experienced as a registered sex offender.

Coerced False Confessions

Another source of wrongful conviction is ‘false confession.’ This is likely to occur when investigators conduct prolonged interrogations with deceptive and coercive tactics. In 1985 the prosecution sought the death penalty when Byron Halsey was charged with the murder and rape of two young children in Plainfield. The mutilated bodies of the children resulted in a horrific crime scene with dramatic media coverage. Halsey was the live-in boyfriend of the children’s mother and thus a likely suspect. Halsey was interrogated for two days and reportedly 'confessed'.

However, there was no objective record of the questioning that led to Halsey's admission. Halsey's confession was inconsistent with the physical evidence, so the interrogating officers wrote a statement that incorporated the evidence, which Halsey signed. Halsey asserted his innocence before going to trial.

He was convicted on several counts but spared a death row sentence because he was not convicted on the highest charge. He filed several appeals but was denied relief. In 2007 he was exonerated after serving 19 years in prison.

Vanessa Potkin from the Cardoza Law School Innocence Project sought and obtained testing of the biological evidence from the crime scene. It did not match Halsey, but it did match a man (Cliff Hall) serving a prison sentence for other sexual assaults in New Jersey. Cliff Hall had lived in the same building with Halsey and the child victims and had testified for the prosecution at Halsey's trial.

Suggestive Questioning of Children

In 1988, Margaret Kelly Michaels, a white woman in her mid-twenties, was convicted of 115 counts of child sexual abuse alleged to have occurred at a church-based, daycare center in Maplewood.

At trial, children testified they had been sexually violated with knives and other kitchen utensils. Despite the fact the church minister, custodians, and secretaries observed no signs of such abuse and medical examinations produced no evidence of injury, the prosecution convinced the jury the crimes were convicted by Michaels.

Margaret Kelly Michaels was sentenced to 47 years in prison. In 1993, Michaels’ conviction was reversed by the appellate courts noting, among other things, the suggestive and leading questioning of children used to elicit evidence against Michaels.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, the wrongful conviction of Michaels was part of a child sexual abuse panic that led to the wrongful conviction of at least 59 defendants around the country in the 1980s and 1990s.

In subsequent appellate litigation, a friend of the court brief prepared by academic psychologists explained how investigators could ‘manufacture’ incriminating accusations from children through introducing sexual content to interviews, rewarding incriminating content and ignoring other content, using a particular tone of voice in the questioning, and encouraging children to help the police.

Coerced Witness Testimony

Kevin Baker and Sean Washington

Baker and Washington were convicted of a double murder that occurred in Camden in 1995. The prosecution’s case relied on one eyewitness who reported she observed the defendants commit the crime.

Baker and Washington were exonerated via the representation provided by the Last Resort Innocence Project at Seton Hall University Law School.

Years of complex appellate litigation established the convictions were the result of false accusations, false and/or misleading ballistic and medical testimony, and inadequate defense representation at the original trial.

The post-conviction investigation revealed the state’s key witness was under the influence of crack cocaine at the time she claimed to have observed the crime, her testimony was inconsistent, and contrary to other witness reports. The record strongly suggested her incriminating testimony was a product of coercion by police investigators.

Baker and Washington were imprisoned for 24 years prior to their release in 2020. Both Baker and Washington have filed claims for state compensation which are pending.

Reforms and Remedies

The legal and criminal justice community in New Jersey have introduced reforms to address the problem of wrongful conviction. In 1999, New Jersey Supreme Court Justice James Coleman wrote the State v. Cromedy decision authorizing special cross-racial identification jury instructions.

In 2001, New Jersey Attorney General, John Farmer introduced new guidelines to ensure that officers who conduct line-ups and photo spreads do not know which person is the prime suspect. To address the problem of coerced false confessions, since 2007, the State Supreme Court and legislature have required that when suspects are in police custody, all questioning must be electronically recorded.

And, in State v. Henderson (2011), the New Jersey Supreme Court adopted procedures for evaluating eyewitness testimony, including a pretrial hearing where the defense can present expert witness testimony challenging the reliability of identifications.

Despite these reforms, there remain concerns that there are many innocent people who deserve exoneration. For instance, Eddie Talbert has been designated a sexually violent predator and is confined at the New Jersey Adult Diagnostic and Treatment Center.

Eddie Talbert asserts his innocence, explaining his original conviction was based on a coerced false confession and biased witness identification procedures, characteristic of the Camden police in the 1980s. Similarly, Ronald Long’s death sentence and conviction were reversed but he awaits his full exoneration related to a jailhouse witness’ false accusations against him.

Today professionals and the public are more aware of the problem of wrongful conviction. Now that DNA testing has become a standard part of criminal investigation, it typically occurs pre-trial thus preventing wrongful convictions in some cases.

The investigation of wrongful convictions has exposed eyewitness misidentification, ‘false confessions,’ police response to press and public pressure, unreliable ‘scientific’ testimony, witness coercion, and the discounting of alibis, as potential sources of error.

The overrepresentation of African Americans among the wrongfully convicted remains a huge concern in New Jersey as well as other states. Research suggests Black defendants are at increased risk of wrongful conviction due to increased police surveillance, explicit and implicit racial bias (affecting judges, juries, attorneys, and the press), limited access to quality legal representation, as well as cross-racial misidentification. What has been learned from confirmed wrongful convictions can further the advocacy for other deserving cases.

*Any opinions expressed in this article are those of the author/s and do not reflect the opinions of Public Square Amplified.